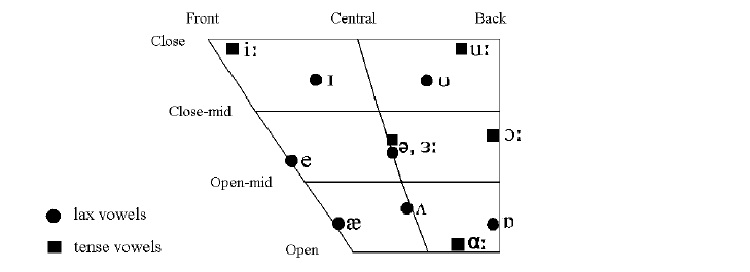

The English language makes a distinction between “pure vowels”, or monophthongs, on the

one hand (i.e. lax vowels: /æ, e, ?, ?, ?, ?, ?/, and tense vowels except diphthongs: /?:, i:, ?:,

u:, ??/), and diphthongs on the other, which are all tense vowels: /??, ??, ??, ??, a?, e?, e?, a?/(3).

As far as production skills only are concerned, diphthongs are not so problematic for EFL

learners, since they are just glides from one vowel sound to another, and misproductions are

mostly due to spelling influence. The real problem concerns pure vowels, i.e. the distinction

between lax vowels and tense vowels that are not diphthongs, commonly (albeit not rightly:

Roach, 2009) referred to as “short” and “long” vowels respectively. On the contrary, French

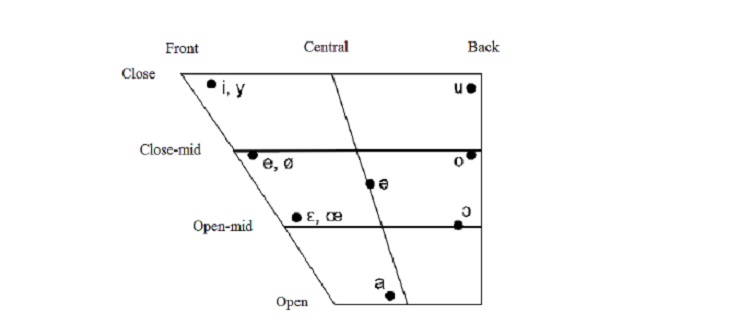

only has a single type of vowel, and vowel duration is the same for all them. The two figures

below show English and French vowels. The principal characteristics of vowel articulation

are found, such as the places of articulation: backness (front vs. back), and height, or aperture

(close vs. open). Lip roundedness is only relevant in the French vowel diagram because it is

the only distinctive feature of some phonemes, while in English, the front/back distinction

already implies unroundedness/roundedness respectively, except for unrounded /?/

(Deschamps et al., 2004). Thus, where there are two vowels in Figure 2, the one on the left is

unrounded, and the one on the right is rounded. French nasal vowels are not represented:

Figure 1: English monophthongs, adapted from Roach (2009)

Figure 2: French oral vowels, adapted from Deschamps et al. (2004)

As is shown by these two figures, despite the frequent use of a unique phoneme in the two

systems, most vowels are articulated differently in English and in French. For example, the

one phoneme /e/ is much closer, or higher, in French than in English, which evinces the fact

that the French word bête is by no means homonymous with the English word bet (not to

mention the phonetic realizations of /b/ and /t/). It is thus acknowledged that it is the

phonetic realizations that are a great source of problem for French EFL learners (Mortreux,

2008), and the latter are not conscious of the differences.

The unavoidable production errors are well-known; the lax/tense distinction is neutralized,

and two English vowels become one French vowel. Mortreux (idem) carried out an analysis

of the recurrent errors made by French learners by transcribing the recordings of two French

students’ productions of English, and using questionnaires to phonetics teachers. To quote

just a few examples, the /æ/-/?:/ pair is replaced by the French phoneme /a/; /?/-/i:/ become /i/;

/?/-/?:/ become /?/ (Herry-Bénit, 2011). As a consequence, one pronunciation has at least two

possible corresponding words, creating confusion in minimal pairs: live and leave are both

pronounced /’liv/. Contrary to what French learners usually think, this substitution will be

more likely to be understood as leave – as is shown in Figures 1 and 2, the French /i/ is much

closer to the English /i:/ than to /?/, which itself would be “better substituted” by a French /e/.

In other words, instead of using the unique pronunciation /’liv/ for both live and leave, a

substitution of live with French /’lev/ would turn out to be better understood by native

speakers of English, provided that the rest of the utterance is grammatically correct. Collins

and Mees (2008) explain that these two English phonemes are heard as if they were

allophones of the one French phoneme by French speakers(4), and that learners must learn to

make contrasts. That may account for the use of minimal pair drills by English teachers in

France. However, as is rightly noted by Brown (1995), the teaching of phonemic contrasts

through minimal pairs has some shortcomings, and intelligibility is not necessarily affected

by such neutralizations as the example of live/leave.

In most, if not all, cases implying a possible confusion in a minimal pair, such as

pronouncing leave instead of live, Brown (idem: 171) notes that the context plays a significant

role, as it enables the hearer to disambiguate the item. That is why he firmly believes that

mispronunciation involving a minimal pair does not lead to unintelligibility. The fact that the

verbs live and leave are followed by different prepositions and often occur in different

grammatical tenses or aspects (I live in London vs. I’m leaving for London) is decisive and seems

to preclude cases of misunderstanding or ambiguity. Similarly, Nakashima (2006) uses the

example of Japanese EFL/ESL speakers, who would most likely substitute the English /r/

with /l/ in the sentence I would like to eat rice. If a Japanese speaker says lice instead of rice, the

utterance is still understandable since Japanese people are not used to eating lice.

Nonetheless, the author also points to the chance that a native English hearer who is not

aware of the Japanese culture, might actually think that it is lice the non-native speaker is

talking about. Lemmens (2010) takes up the live-leave pair, which he asserts can lead to

misunderstanding even though the prepositions are different. If a French speaker says he

“leaves” in London instead of he lives in London, an English speaker might conclude that the

French speaker meant he leaves for London. In other words, it cannot be ascertained that a

native speaker will mentally correct live/leave, but perhaps they will mentally correct the

following preposition. Such an example implies that minimal pairs can lead to

misunderstanding, but also to grammatical mistakes.

The impact of misproduction of English segments on intelligibility and communication

often involves two members of a minimal pair. One of the few other consequences, also true

of suprasegmental misproductions, is foreign-accentedness, which, as was said above, does

not systematically causes unintelligibility. However, this seemingly unimportant detail can

prove to be an impediment to communication. An EFL or ESL speaker’s having a strong

foreign accent might lead to the native English speaker’s simply abandoning communication

by dint of accumulating mental corrections (Lemmens, 2010). Furthermore, it is the cause for

many stereotypes (Mennen, 2006; Vergun, 2006), be they good or bad.

This account of some segmental difficulties for French EFL learners and the impact on

production and intelligibility has deliberately overlooked the widespread problem of the

phoneme called “schwa”. In fact, it corresponds to the phenomenon of vocalic reduction,

itself being a consequence of the rhythm of English and the stressed/unstressed alternation

(Huart, 2002). That is why Brown (1995) classifies vowel reduction and the schwa among

suprasegmental features. The following subsections thereby deal with suprasegmental

difficulties for French learners, including intonation – and particularly tonicity –, stress,

vowel reduction, and rhythm. The stress-timing/syllable-timing typology of languages is also

looked at, for it is a basis for the understanding of the difference between the English and

French prosodic systems.