“In fact, it’s competition among business ecosystems, not individual companies, that’s largely fuelling today’s industrial transformation. Managers can’t afford to ignore the birth of a new ecosystem or the completion among those that already exist”. James F. Moore, Harvard Business Review, May-June 1993: 56

2.1. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1.1. Introduction

No firm can ignore the impact of globalisation. By its nature, involving as it does the increasing integration of national economies into the international economy through for instance trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), labour migration etc., the development of technology and telecommunications, transnational circulation of processes, ideas etc. can be spread widely. Firms competing for efficiency or for market strategy, create an environment of competitiveness . African MNCs also by joining the game, aim or hope to achieve supremacy both inside and outside their boundaries, although the financial industries in which they operate suffer from diseconomies of scale caused by narrow markets in each country (World Bank report, 2007).

2.1.2. Theories development

Competitive advantage (Porter, 1990) is what enables a firm to turn one or more specific resources controlled by it with greater success than any other competitor in the same field (Ma, 2000: 53) .Competitive advantage involves “the strategies, skills, knowledge, resources or competencies that differentiate a business from its competitors” (Daniels et al., 2011: 838). This underlines elements of positioning helped by several variables and interactions present in the environment of the firm.

However, Porter distinguished two basic types of competitive advantage, the first of which is Cost leadership -the production of similar or higher quality products at a lower cost than its competitors; the second of which is by being unique which is appreciated by consumers. Furthermore in the development of its strategy a firm might decide to target a segment or niche of clientele by adopting one or the two basic strategies leading to two extensions: Cost focus and differentiation focus. All tfirms however cannot easily utilise these strategies for a number of reasons thus pushing them to be stuck in the middle, which is usually a low-profit area, although for some industries it can be a very attractive and lucrative zone.

Competitive advantage is achieved when a firm possesses, “… an organisational embedded non-transferable firm-specific resource whose purpose is to improve the productivity of the others resources possessed it” (Makadok, 2001: 389). This should give it the ability to select, assimilate, exploit, develop and adapt essential and relevant resources external to the firm for its success (Cohen and Levinthal, 1989). Many scholars expand upon the idea, by differentiating resources and capabilities as follows; “Resources are stocks of available factors that are owned or controlled by the organisation, and capabilities are an organization’s capacity to deploy resources” (Amit and Schoemaker, 1993: 35). The capabilities used through a dynamic approach, contribute to the foundation of a sustainable advantage and become integrated in the strategy of the firm in terms of market entry or positioning (Teece, 1992, 1996a; Teece et al, 1994). One of the key aspects of competitive advantage theory is the resource – based view (RBV).

The RBV stipulates that a firm’s competitive advantage lies firstly in the accumulation of valuable resources used by the firm (Wernerfelt, 1984:172; Rumelt, 1984:557-558).

Then their transformation to have an advance which will be sustained over the long run under four attributes called the VRIN model. The first one is valuable, therefore a firm should employ a value-creating strategy to outperform its competitors or to reduce its own weakness (Barney, 1991:99; Amit and Schoemaker, 1993:36); follows by the second is that resource has to be rare (Barney, 1991:100), but not anymore in fashion (Hopes et al., 2003:890); then it should be in-imitable; because mainly and only controlled by the firm (Barney, 1991:107). Therefore the asset becomes strategic for the firm and not easily duplicated by the competitors (Peteraf, 1993:183; Barney, 1986b:658). And finally, it has to be non-substitutable because imperfectly imitable, (Dierickx and Cool, 1989:1509; Barney, 1991:111). However, the VRIN is in need to be always updated in the unpredictable market and environmental conditions creating very quickly obsolescence (Morgan, 2000 on Finney et al. 2004:1722). The Barney’s sustainability definition was attacked but claimed back that the competitive advantage is sustained if current and future rivals have ceased their imitative efforts (Barney, 2001). The RBV approach was extended by others like (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Corner, 1991; Barney, 1991), for them the RBV does not go far enough on the importance of knowledge, which is just used as generic resource to achieve competitive advantage.

Conner and Prahalad went further by suggesting that knowledge-based resources are “…the essence of the resource-based perspective” (1996:477) and was defined as “information combined with experience, context, interpretation and reflection. It is a high-value form of information that is ready to apply to decisions and actions” (Davenport et al., 1998). Anyway, Kogut and Zanger (1993) stated that firms used knowledge to expand and survive across boundaries, also, in this industry wherein almost every one offer the same product the difference will be made on the ability of the firm to understand its own market (Peteraf, 1993:180-182; Mohaney and Pandian, 1992:365; Barney, 1991:110; Lippman and Rumelt, 1982:420), which becomes a source of competitive advantage.

The source of sustainable competitive advantage can be considered on the customer perspectives (Day and Nedungadi, 1994) or for market orientation by adapting with the changes occurring in the customers’ needs, the strengths of competitors and technology (Day, 1994; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). And knowledge for interpreting and assessing the market trends differentiates one firm to another (Fiol and Lyles, 1985) to generate superior strategies leading to innovation (Varadarajan and Jayachandran, 1999). A firm, when growing, the necessity to go out its own boundaries becomes primordial. Go abroad and why, where and how has always been challenging for firms, which the international competitiveness may diverge from its competitiveness in the home countries in which the market is protected by trade barriers and the one totally open to trade. Internationalisation is not linear as developed (Hitt et al., 1997), however the motivation of going abroad are the search of economies of scale and scope (Teece, 1980; Hymer, 1976; Caves, 1971). Nonetheless, it is not clearly established the correlation between internationalisation and performance a date (Lu and Beamish, 2004:599).

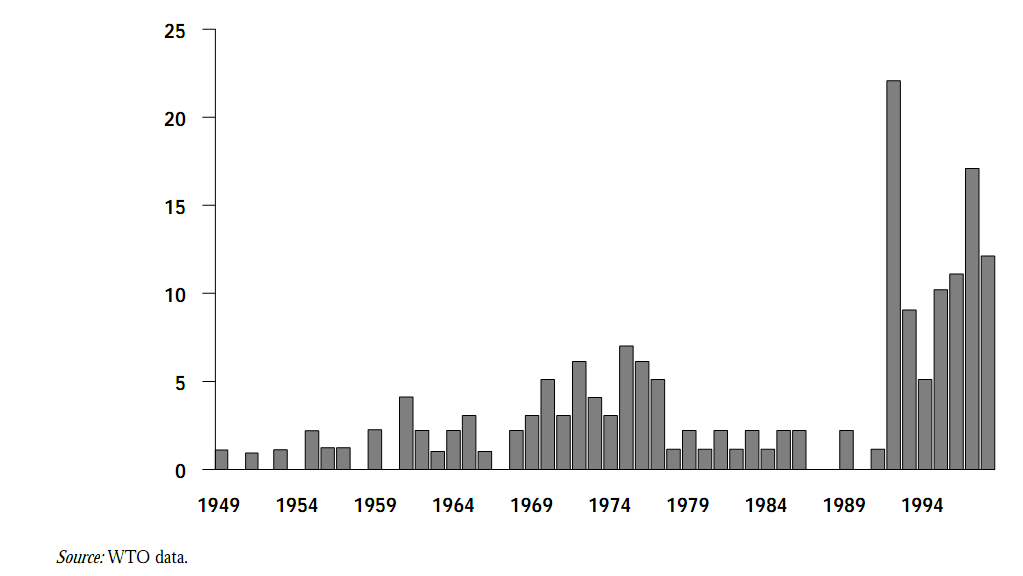

In the international competitiveness, make firms and country to consider in the small economies another model including network approaches, which following the literature can be resolved into regional integration for African countries. As many countries are member of one or more regional integration agreements (RIAs), whether to use a single currency (Eurozone in Europe and Franc CFA IN Africa) or a single market and reduce trade barriers (European Union, ECOWAS or CEMAC in Africa); in the Africa in which oral and narrative tradition is used, impacting on the everyday knowledge and patterns of sharing meanings; which if well-utilised can be a metaphoric root to create and sustain differentiation (Van Maanen, 1991; Young 1989) and succeed in its integration and expansion (Peters and Waterman, 1981; Shein, 1992). In Africa the culture is deeply rooting making connections of any kind as developed Mintzberg, “culture is the soul of an organisation … the beliefs and values, and how they are manifested”. The notion of country and boundaries in the African culture, is altered especially in Black Africa, and creates division among scholars and local leaders (Amadife and Warhoja, 1993: 533-554). However they all agreed on the complexity and interactions of culture while doing business. Moreover, “functional culture area” as an organised area which functions economically, politically or socially without line of differentiation (Brown et al., 2006). This was already spotted by the WTO’s publication (1999), which reported the rise of RIAs around the world, for politically and economically motivations, in the last decades.

Figure 1. The Regional integration agreements progression in the world

Even in the same RIA, Cantwell (1994) differentiated two the nature of the direction of investment by arguing that inter-regional FDI is for increasing market size but the intraregional FDI is most related to increase the market share. Therefore this will facilitate collaboration or network. As suggested Goyal (2009): “networks pervade social and economic life, and they play a prominent role to explaining a huge variety of social and economy phenomena.” In other words, the regional integration works as a network enabling efficiency, bargaining power, strengthen the economy and the market and might help for innovation development. Because the region will create set of tool enabling a general and understandable environment, which will become competitive for inward FDI; according to Vernon (1988: 32-33) who called this kind of interaction “bidding competition” or “beauty contests” (Scott, 1998).

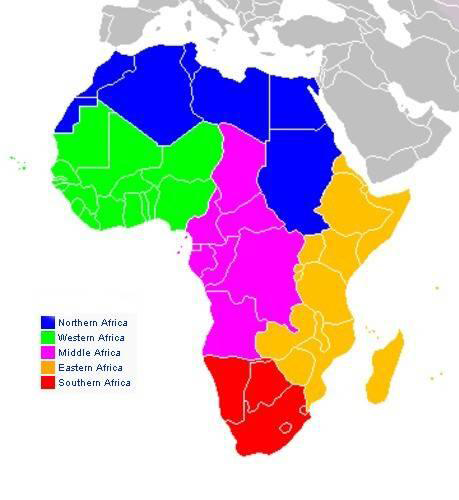

Africa, also do not pale in “beauty competition”, numbers of RIAs in the continent might make researchers breath away. According the United Nations (UN) in 2011, this is the regional map of Africa.

Figure 2. African regions

Source: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#africa (2011)

The Southern Africa in red is wherein located South Africa and the Green part wherein Togo. Many countries in Africa are member on one or many blocs: bloc of currency, bloc of trade, regional bloc, and so and so. The part of Africa in the world Economy was 3 percent in 1950 and represents now just 1 percent (Institute for International Affairs, 2000). In Sub-Saharan Africa, most of countries have small financial industry and are among the smallest in the word, which represents much just fewer opportunities to develop or to diversify. And only South-Africa and Nigeria have a financial sector wealthy and weighting more than $10 billion, leaving those countries with few foreign affiliates and estates banks making the market less competitive, less efficient for their lack of economies of scale. Also the market is incomplete because just a finest population has access to finance. This makes the industry more risky and costly, in the Africa not always stable politically. Therefore, the following of this analysis will be restricted to the related region of the chosen countries.

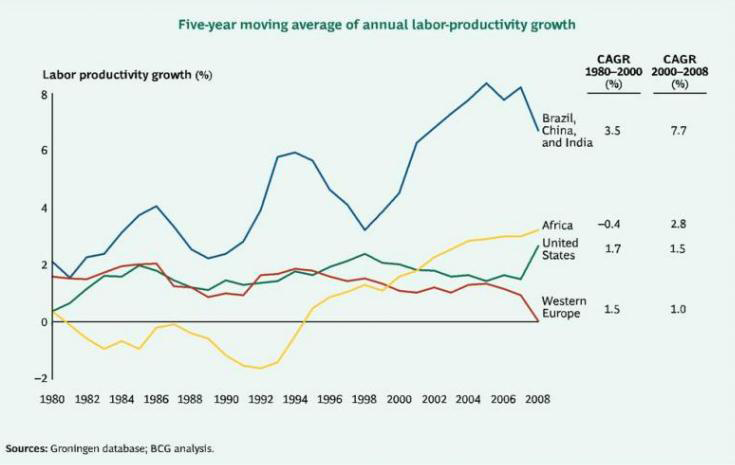

However, African economic is growing according to the following graph, which illustrates the progress of labour-productivity growth; explains by more people having the possibility to get a job in the formal system. Nonetheless, firms in their internationalisation process will use knowledge owned and expertise gained, to expand and survive across boundaries, because it is valua ble to act in a difficult market as Africa and to reach its targets (Kogut and Zanger, 1993) and to likely develop a sustainable competitive advantage to succeed abroad.

Figure 3. Labour-productivity growth comparison

Source : BCG

2.2. CASE BACKGROUND

2.2.1. African Environment

In Africa, in which the structure of the market is difficult to explain, it does not fall fully in all the market structure developed above. The market is deregulated (BCG, 2010); is characterised by: “…technical and managerial skill scarcity … the cost of domestic capital is high… poor governance … access to international market very high and costly … complete disorder and no real rights on ownership of land, which is kept through a unclear system…” (Tumusiime-Mutebile, 2010) also corruption, non-transparency and political conflicts are making the market to be non-organised (Grindle, 2004); or presence of poverty, lack of trade facilitation, lower access of educational knowledge, volatility, political instability in many countries, market imperfection to play the game of competitive solutions development (Collier, 2007). The continent still struggles for stability, for example the split of Sudan analyses by (Clarke and Heavens, July 2011) qualified of “messy divorce”. Separation was done after long run fight and lot of blood. This summary illustrating in 2010, conflicts around the world and avoid putting more colour in a paint over-coloured.

Figure 4. Conflicts’ map of Africa

Source: Virgil Hawkins, New World Maps, Stealth Conflicts, December 30, 2008

At the governance level, Gringle recognised the benefits of good governance on the development and fight against poverty in a country. Also confirmed by the US Ambassador at the United Nations Thomas R. Pickering on October 28, 1991: “Reforms to improve governance are essential, both for sustainable economic growth and political stability …. The bottom line of good governance is democracy itself. It is not our role to decide who governs any country, but we will use our influence to encourage governments to let their people make that decision for themselves”, reforms in Africa which are very slow; even “while some African countries have advanced…” in “transparency and corruption eradication” (The World Economic Forum (WEF), 2010; The National Democratic Institute (NDI), 2007). In instance, the (NDI) working to strengthen countries in many aspects in which the East African Legislative Assembly (EALA) supported to develop transparency and accountability in the natural resources industries. Others “have significantly deteriorated”. Therefore the continent’s markets were agreed to be classified by scholars of imperfect, (Vatiero, 2009; O’Sullivan, 2004 and 2003; Sheffrin, 2003). The market imperfection reveals a failure of efficiency in allocation of production.

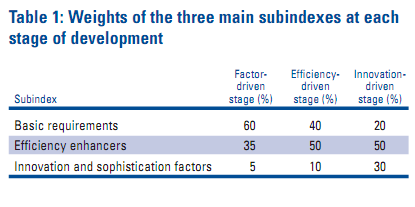

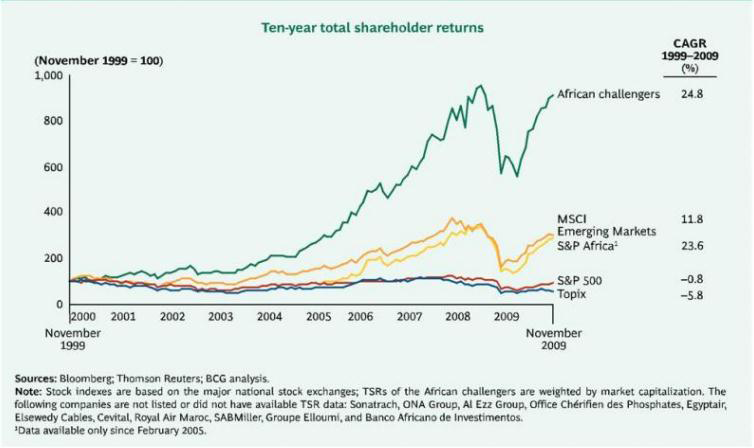

Market imperfection is defined as anything interfering with trade, (DeGennaro, 2005:12). Some MNCs owe their existence to market imperfections was first put forward by (Hymer, 1960/1976; Caves, 1971), qualified to come from structural deviations from perfect competition in the final product market due to exclusive and permanent control of proprietary technology, privileged access to inputs, scale economies, control of distribution systems, and product differentiation, but in their absence markets are perfectly efficient and confirmed to be used as tool of competitiveness in the African environment (BGC, 2010). The WEF in their global competitiveness report of 2010-2011, determined 12 pillars which can be grouped into three categories, explaining the driving factors of the country and international competitiveness based on the weight as follows:

Table 2-1. Weights of competitiveness sub-indexes

Source: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2010-11.pdf

Figure 5. Pillars of competitiveness and meanings

Source: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2010-11.pdf

Productivity is a domestic mater, so countries do not have that importance in economic competition (Krugman, 1998), but it can create an environment to enable industry and firms to succeed in the international competition, precisely in African market and its specificities. Nonetheless, the assessment of international

competitiveness of domestic firms in Africa, shows the flows of FDI in both ways (from outside the region and within the region) (Wells, 1977/1981; Kumar and Lim, 1984; Hoesel, 1999); and many studies were conducted to prove the nature of expansion of developing countries’ firms to those coming to developed countries, (Dunning, 1986); confirmed by Kumar which noticed the rapid grow of the FDI coming from developing countries from the mid-1980s. Usually categorised by the researchers as cost effectiveness MNCs (Dunning et Al) but latterly, it has been noted some interrelated points of convergence between the different categories (Dunning, Van Hoesel and Naruala, 1997; van Hoesel, 1999), with the venue of the new technologies, in the transactions and venture direction of firm (Van Hoesel, 1997).

2.2.2. BCG Report and Conclusions

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG), a consultancy group founded in 1963, is a well – known firm around the world, with its seventy offices in forty-two countries. The African interest of BCG is not a new trend, it is totally integrated onto a long process of study in developing countries, with many publications such as: “The 2009 BCG 100 New Global Challengers: How Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Contending For Global Leadership” (2009), focusing in the fast growing firms in developing countries or “The 2009 BCG Multilatinas: A Fresh Look at Latin America and How a New Breed of Competitors Are Reshaping the Business Landscape” focusing on firm in South-America.

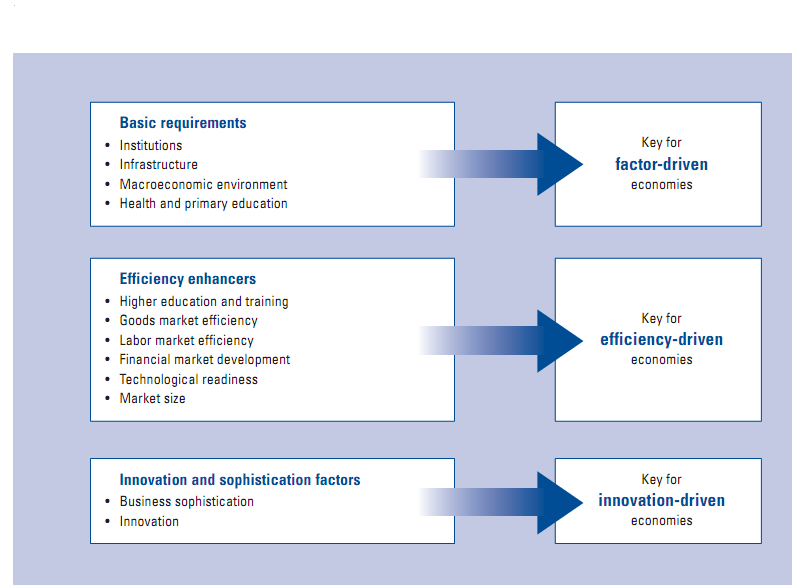

The “40 lions” was called in reference of “the tigers” in Asia. And the selection was made in a very rigorous manner “… on the basis of socioeconomic factors, including GDP per capita, standard of living, ease of doing business, political stability, and public investment in a safety net… To arrive to the top African 40 challengers challenged over 600 companies examined covering all economic sectors”; in many different stages which are illustrated in the following table.

Table 2-2. Selection methodology

Source: Author; Modified version of BCG Table

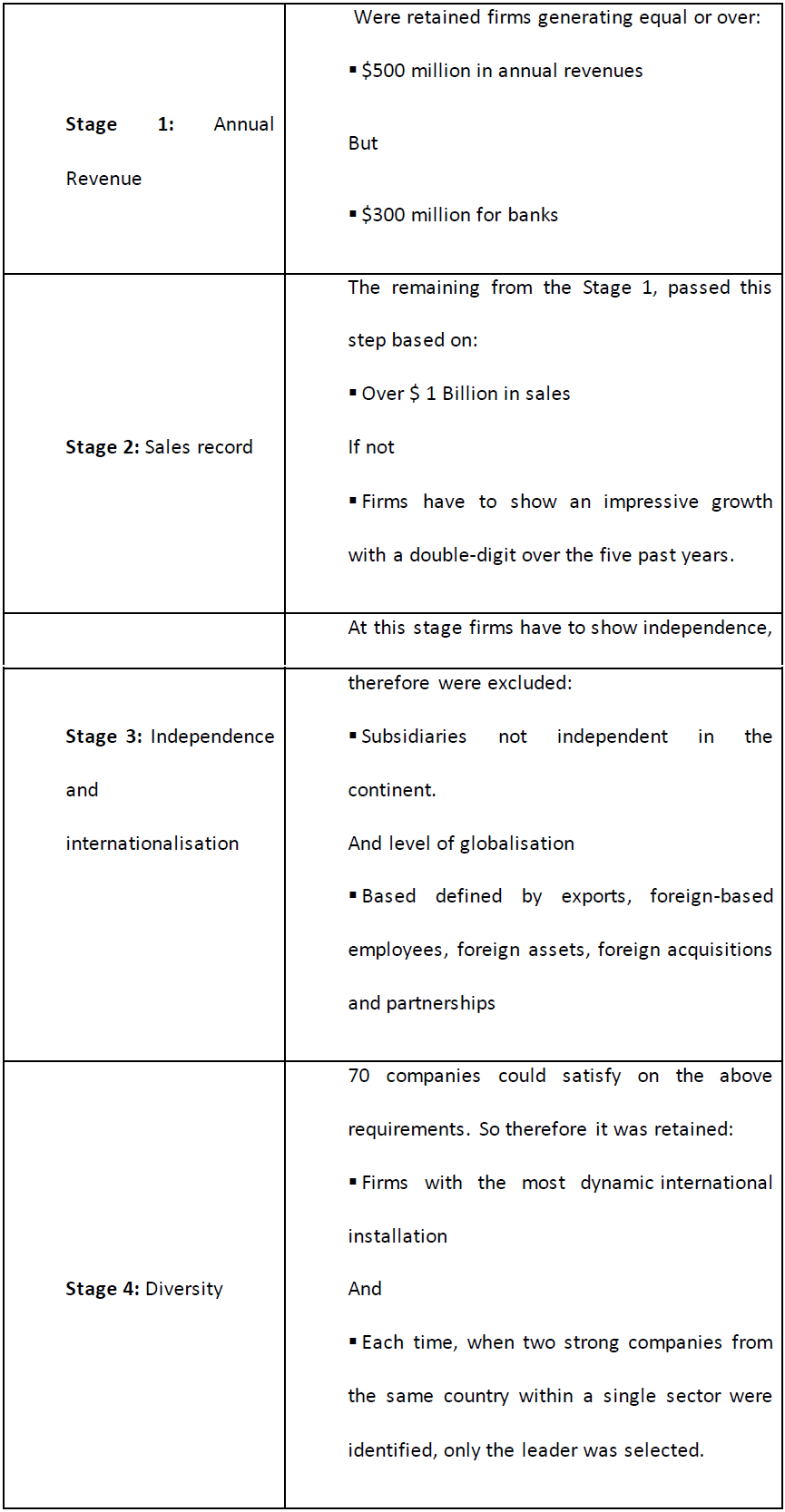

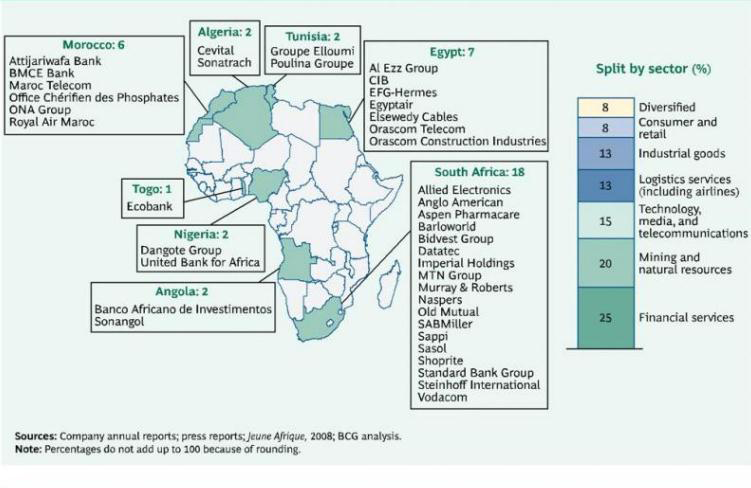

“At the end of the process, forty firms were identified and selected, they range in size from $350 million to $80 billion in annual sales; they all display strong growth, an international footprint, and ambitious plans to further overseas expansion; and five countries (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria and South-Africa) taking a beauty part in shares of number of the growing companies; nevertheless, can be noted, the disparate repartition of companies and the dominance of three countries of origin: 18 South African firms, 7 Egyptian and 6 Moroccan for the top of the list; were living in a no well-known or long time borderlined continent. However, the returns are above other developing countries and even within the BRIC”.

Figure 5. Shareholders returns comparison

Source: BCG Report 2010

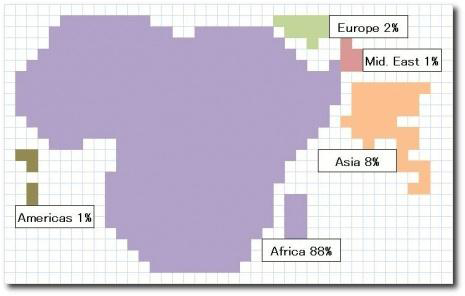

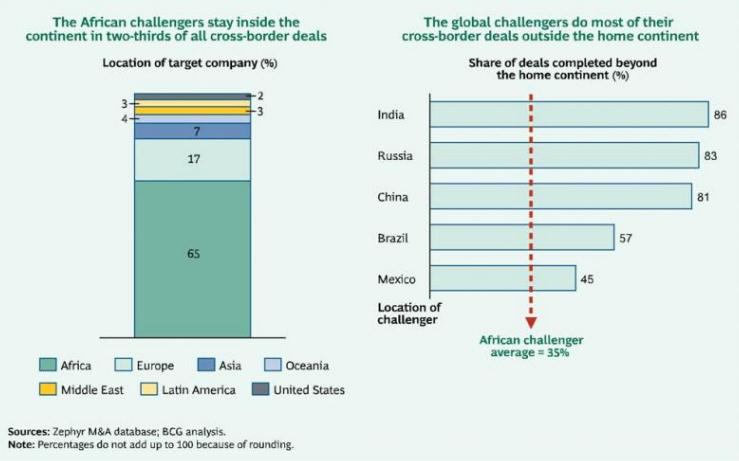

More after, it had been shown that these firms have for particularity to stay inside the continent and services have a great place in term of percentage.

Figure 6. Cross-border deals illustration

Source: BCG Report 2010

The financial sector, the main interest on this dissertation, takes the lead in the continent and represents twenty-five percent.

Figure 7. Split of the African challengers by sector and by country

Source: BCG Report 2010

The African banking system and financial services features are still depressing and are associated to heterogeneities some coming from the colonial system or the history of Africa. Despite the regionalisation and integration, divisions remain such as: Nigeria, South Africa and the rest of the Anglophone countries taking their own directions some in the south by refastening the South African umbrella; the Francophone African countries and the rest of countries. With the rate of coverage of least than five percent the Sub-Saharan African people has an bank account, however some changing are happening, which will push perhaps the rapid change of the industry, despite remaining problems in the political level, macroeconomic level and governance.

However, while some African challengers and foreign firms see each other as:

– Partners: in instance of Vivendi, while ventured in Morocco decided to take a control of a local firm, the well implanted Maroc Telecom therefore using their

knowledge for a better success.

Others adapted and behave in a different way, as,

– Competitors: for example, Orange the telecommunication company see MTN as a strong and serious competitors within the market. Notwithstanding, African challengers are benefiting from many key factors according to BCG:

a) Native advantages: which are at first a chance to operate in their originally market, cumulated with abundant factors of endowments such as: natural resources which are abundant; labour cheap, available and abundant; and population which is rapidly growing. Then the legacy of languages coming from the

first contact with westerners, technology and systems shared and imported over the time.

b) Business environment: including market deregulation leading to volatility in the market, which associated to national economic-development policies makes the standards of trade agreements not fully implemented but countries tending to ratified and taking measures of implementation and adaption into the educational system for a better comparison and adjustment to the need of the employment market. Also, can be added the increase of commodity prices for instance petroleum or telecom industry giving a greater return for African challengers.

c) Revenge mind-set: with their willingness to prove their ability by undertaking bold and creative by succeeding in a challenging economic environment.

Strategically, African challengers use their creativity to adapt to their context by developing innovative product and under challenging conditions, they build unusual type of business model, and when they venture searching for a long term return.

2.3. CONCLUSION

The study of international competitiveness of domestic firms in developing countries revealed the Africa is understudied and in the world wherein the globalisation is a moving and complex element, impacting western firms which some of them have intercorrelation and connection in the “continent of origin”. Notwithstanding, Africa is a huge support in the world economy, since the dawn of time, part of capitalisation of various industries, in instance the “trans-Atlantic trade” from far days and nowadays in oil industry. Oil, Gas or Electricity are some products that we use in our daily life without a think of not having it for the next hour. These goods are not just for our convenience, they made the world economy turn from a services based offices to the markets places in which all the sophisticated programs and computers need information coming from across the globe. For example, Areva, the French worldwide company leader in the nuclear energy needs its resources from Niger (Jewell, 2011) and many firms such as British Petroleum, Total, etc… have their source of revenue and resources coming from this continent (Vicente, 2010). However just few researches were made, to examine the strength and opportunities of African potential even thou they were behind, for the development of companies able or wanting to trade worldwide. In a very long run of disputes many theories explaining how to do competition but is retained two hypotheses enabling to examine and analyse issues surrounding the topic, they are:

Hypothesis 1: The more solid is the knowledge of the firm on its local market, the stronger is the driving forces to out-perform against competitors.

Hypothesis 2: the more essential is the knowledge owes by the firm, the more expertise gained, therefore likely to develop a sustainable competitive advantage to succeed abroad.

By exploring the above areas of literature, a better understanding on the singularities evolving in the African competiveness by using the market deregulated and which the competition is imperfect with the competitive advantage as canal alongside of which the resources base view in the axe of knowledge by which firms achieve a sustainable advantage while they compete internationally. In the following chapters, this study will carry out an analysis based on the South African Standard Bank and the Togolese Ecobank, companies with different approaches whether in their growth, development or their modes of venture in their respective countries and internationally or just their atypical perception of themselves. And find element of response to how they attain and maintain their competitiveness in all ways.